In the shadowy crossroads where pulp fiction meets conspiracy theory, few substances have captured the modern imagination quite like adrenochrome. It is portrayed as a mysterious, crimson-hued elixir—simultaneously a potent psychoactive drug, an anti-aging panacea for the wealthy and powerful, and a grotesque sacrament harvested from the terror of tortured children.

This content is for informational purposes only and is not medical advice. Always consult a healthcare professional for medical concerns.

Adrenochrome: Medical Facts vs. Myths

A scientific clarification to separate evidence-based information from widespread misinformation

This mythos, a grotesque tapestry woven from threads of real biochemistry, mid-century psychiatric speculation, and contemporary digital folklore, reveals far less about pharmacology than it does about the darkest corners of our collective psyche and the mechanics of disinformation in the 21st century. To separate the molecule from the myth is to embark on a journey through science, cinema, and social contagion.

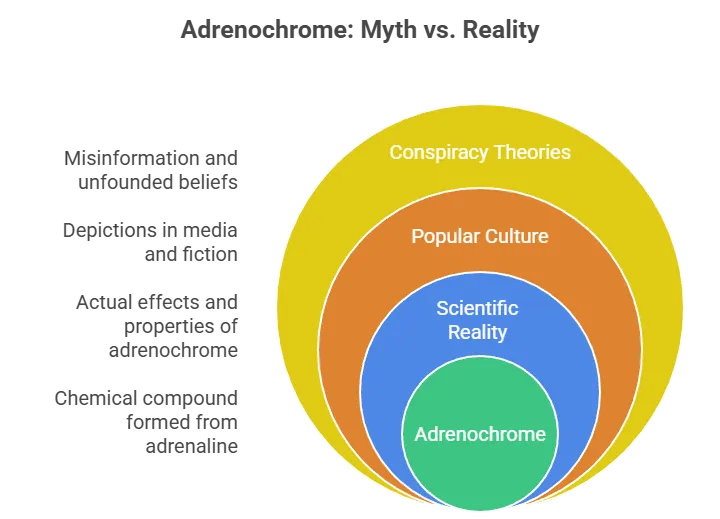

The Biochemical Reality: A Mundane Metabolite

First, we must ground ourselves in fact. Adrenochrome is a real organic compound. It is an oxidation product of adrenaline (epinephrine), the body’s quintessential “fight-or-flight” hormone. When adrenaline is exposed to air, it readily oxidizes, turning a distinctive shade of pink and then brown, much like a sliced apple. This process yields adrenochrome.

Discovered in the laboratory in the 1930s, adrenochrome is an endogenous metabolite, meaning it occurs naturally in the human body in trace amounts. Its pharmacological profile, however, is a far cry from the mythic properties assigned to it.

Early, poorly-controlled psychiatric research in the 1950s and 60s, notably by Humphry Osmond and Abram Hoffer, hypothesized that adrenochrome might be a psychotomimetic—a substance that mimics psychosis. They speculated it could be an endogenous schizotoxin, contributing to the symptoms of schizophrenia.

This “adrenochrome hypothesis” was part of a broader, ultimately abandoned, theory of chemical imbalances. Subsequent, more rigorous studies failed to substantiate these claims.

While some self-experimenters, like the writer William S. Burroughs, reported mild hallucinogenic or dissociative effects from synthesized adrenochrome, these accounts are anecdotal, inconsistent, and confounded by the use of other substances.

The scientific consensus is clear: adrenochrome has no significant, reliable psychoactive effects in humans worthy of a “drug” classification, no proven therapeutic benefits, and certainly no life-extending properties.

The myth’s first layer of illusion, therefore, is one of alchemical transformation: it takes a mundane, scientifically unremarkable metabolite and imbues it with magical potency.

The allure begins with its origin story—born from adrenaline, the very essence of primal fear. This provides a poetic, if scientifically tenuous, hook: that the essence of terror could be distilled into a tangible substance.

The Literary and Cinematic Crucible: Fiction Fertilizes Fantasy

If science provides the raw material, literature and film provided the narrative crucible. The myth’s most significant forge was not a laboratory, but the pages of Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception (1954) and, most indelibly, Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971).

Thompson’s semi-autobiographical, psychedelic satire cemented adrenochrome in the counterculture lexicon. In a famously grotesque passage, his alter-ego Raoul Duke describes it as “the ultimate high,” harvested from the adrenal gland of a living person.

“The adrenaline glands from a living human body,” Duke’s attorney Dr. Gonzo explains. “It’s no good after the person dies.” Thompson, a master of gonzo journalism, was using adrenochrome as a literary device—a hyperbolic symbol for the depraved extremes of the drug culture and the corrupt American Dream. It was satire, a dark joke about the lengths to which the pursuit of sensation might go.

This fictional trope was then amplified by popular cinema. The 1978 film *The * and its 2018 sequel Halloween feature a psychiatrist, Dr. Sam Loomis, who describes his patient, Michael Myers, as possessing a rare condition: “pure evil,” with eyes described as “the blackest eyes – the Devil’s eyes,” a description some fans later loosely (and inaccurately) connected to the effects of a fictional adrenochrome.

More direct was the 1998 film Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, which brought Thompson’s vivid description to a wider audience. Crucially, these works presented adrenochrome not as a clinical curiosity, but as a secret, forbidden, and profoundly dangerous substance—a narrative frame perfectly suited for conspiracy.

The Conspiratorial Metamorphosis: From Satire to Sacrament

The transformation of adrenochrome from a literary metaphor into a central pillar of a sprawling conspiracy theory is a phenomenon of the digital age. The myth found fertile ground in the online incubators of the early 21st century, particularly on forums like 4chan’s /pol/ (politically incorrect) board. It was here that the scattered pieces—the real chemical name, Thompson’s fictional harvesting method, and pre-existing anti-Semitic and elitist tropes about blood libel and secret societies—were synthesized into a new and monstrous whole.

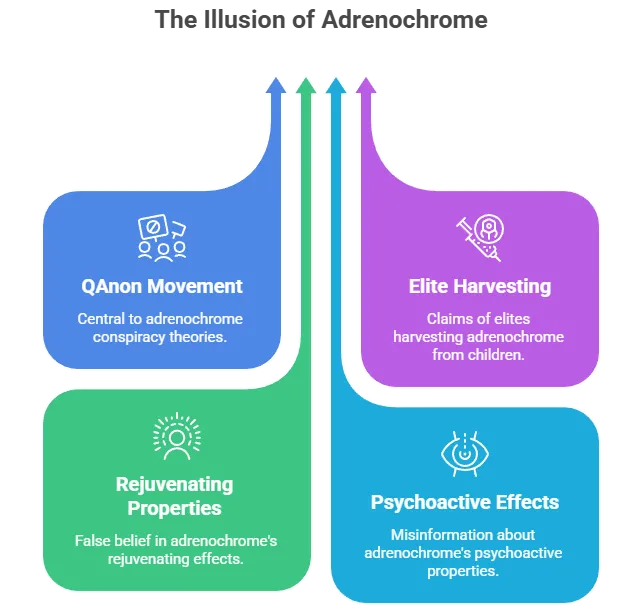

The modern adrenochrome conspiracy theory posits that a global cabal of elites—politicians, Hollywood celebrities, and wealthy financiers—are secretly engaged in the torture, murder, and harvesting of children to extract adrenochrome from their adrenal glands.

This substance, the theory claims, is then used as a powerful drug that grants youth, vitality, and transcendent experiences, binding the corrupt elite together in a pact of unspeakable evil.

This narrative serves multiple psychological and rhetorical functions:

- Moral Alchemy: It transforms political or cultural opponents into literal monsters—not just people with differing ideologies, but pedophilic, murderous cannibals. This justifies extreme hostility and dehumanization.

- Explaining the Unexplainable: It provides a simple, if grotesque, answer to complex questions: Why are the rich and powerful successful? Why do some celebrities seem to age well? The answer is not genetics, wealth, access to healthcare, or plastic surgery, but a magical elixir derived from unspeakable acts.

- Mythic Resonance: The theory directly echoes ancient “blood libel” accusations against Jews and other marginalized groups, which claimed they used the blood of Christian children in rituals. It also taps into archetypal fears of secret societies engaging in dark sacraments, from the legends of the Illuminati to the mythology surrounding the fictional Eyes Wide Shut.

- The Thrill of the “Red Pill”: Believing in such a deeply hidden, horrifying truth fosters a sense of secret knowledge and superiority. The adherent becomes a brave truth-teller in a world of sleeping sheep.

The theory reached its apotheosis in the QAnon movement, where adrenochrome became a key piece of lore. QAnon’s vague prophecies of “The Storm” and the arrest of a “global cabal” often implicitly or explicitly referenced the harvesting of children for adrenochrome as the ultimate proof of the cabal’s depravity.

This digital folklore escaped the confines of niche forums and entered mainstream discourse, repeated by influencers, politicians, and millions of followers.

The Human Cost: Beyond the Illusion

While the adrenochrome myth may seem like a bizarre fantasy to outsiders, its consequences are profoundly real. The illusion has tangible, damaging effects:

- Harassment and Violence: Believers have harassed and threatened individuals they falsely accuse of being part of the conspiracy, including politicians, celebrities, and private citizens. The 2016 “Pizzagate” shooting, where a man fired an assault rifle in a Washington D.C. pizzeria he believed was the front for a child-trafficking ring, is a direct precursor and parallel to the adrenochrome narrative.

- Undermining Real Justice: The fantastical noise of the adrenochrome theory drowns out the sober, critical work of addressing very real, documented issues of child exploitation and human trafficking.

- It provides a caricature that allows cynics to dismiss all concerns about elite misconduct as the ravings of conspiracy theorists.

- Erosion of Epistemology: The myth thrives in an ecosystem that rejects evidence-based reasoning.

- It represents a triumph of narrative over fact, where a compelling story, regardless of its truth, becomes a unifying identity. This erodes the shared reality necessary for a functioning society.

- Trauma for Victims: For the actual victims of childhood trauma or trafficking, seeing their profound suffering co-opted into a lurid, sci-fi-tinged conspiracy theory is a form of secondary victimization. It turns their real pain into a plot point for a collective delusion.

Conclusion:

The Elixir of Belonging in a Disenchanted World

In the final analysis, adrenochrome is undeniably an illusion. As an elixir of youth or a super-potent psychedelic, it is a biochemical phantom. But as a cultural object, it functions as a different kind of potent brew: an elixir of meaning, belonging, and simplified outrage for those who feel alienated, disempowered, and disillusioned by a complex world.

The persistence of the myth teaches us that in an age of information overload, the most powerful narratives are not necessarily the truest, but the most resonant.

It demonstrates how fiction can be weaponized, how ancient prejudices can be recoded in pseudo-scientific language, and how the human need to find patterns and villains can override critical thought.

The adrenochrome saga is a dark fairy tale for the internet age, a warning that when the lines between satire, speculation, and sincere belief are irrevocably blurred, the monsters we create in our collective stories can step off the screen and into our courts, our politics, and our streets.

The real terror, it turns out, is not in a mythical molecule, but in the profound human capacity to believe in it.

This response is for reference only.

Here are key scientific citations that address the biochemical reality of adrenochrome and the psychiatric research that fueled the initial speculation, which was later contradicted by more rigorous studies.

1. Early Research & The "Adrenochrome Hypothesis"

These papers established adrenochrome as a compound and proposed its potential role in psychosis, forming the scientific kernel that later myths distorted.

- Discovery and Initial Characterization:

- Green, D. E., & Richter, D. (1937). Adrenaline and adrenochrome. Biochemical Journal, 31(4), 596–616. This is one of the foundational papers describing the oxidation of adrenaline to adrenochrome.

- Hofmann, A. (1961). Chemical, pharmacological and medical aspects of psychotomimetics. Journal of Experimental Medical Sciences, 5, 31–51. Includes discussion of adrenochrome alongside more potent psychedelics like LSD, noting its weak and unreliable effects.

- The Osmond-Hoffer Hypothesis (Psychotomimetic Model):

- Hoffer, A., Osmond, H., & Smythies, J. (1954). Schizophrenia: A new approach. II. Result of a year's research. Journal of Mental Science, 100(418), 29–45. This paper outlines the early hypothesis that adrenochrome, as an endogenous metabolite, might induce a model psychosis resembling schizophrenia.

- Osmond, H., & Smythies, J. (1952). Schizophrenia: A new approach. Journal of Mental Science, 98(411), 309–315. The seminal paper that first proposed the concept of a "hallucinogenic" endogenous metabolite.

- Hoffer, A. (1967). Adrenochrome in blood plasma. American Journal of Psychiatry, 124(5), 114–119. Reports on attempts to measure adrenochrome in patients, though methods were later criticized.

2. Refutation and Failed Replication

Later, better-controlled studies failed to confirm the psychotomimetic effects or the hypothesis that adrenochrome played a role in schizophrenia.

- Lack of Psychoactivity in Controlled Studies:

- Grof, S., Vojtěchovský, M., Vitek, V., & Prank, S. (1963). Clinical and experimental study of central effects of adrenochrome. Journal of Neuropsychiatry, 5, 33–50. A controlled study finding no significant psychoactive effects of adrenochrome in human volunteers.

- Hordern, A., & Mroczek, N. (1960). The effect of adrenochrome and adrenolutin on the behaviour of the rat. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 23(1), 56–60. Found no significant behavioral effects in animal models.

- Kety, S. S. (1959). Biochemical theories of schizophrenia. Science, 129(3362), 1528–1532; 1590–1596. A major critical review that seriously questioned the methodological flaws and lack of solid evidence for the adrenochrome hypothesis and other biochemical theories of the time.

- Scientific Consensus and Review Articles:

- Smythies, J. R. (1976). The role of dopamine in schizophrenia. In Biological Psychiatry 1975. Springer. (Later work by one of the original proponents shifted focus to dopamine, reflecting the abandonment of the adrenochrome hypothesis).

- Healy, D. (2002). The Creation of Psychopharmacology. Harvard University Press. Provides historical context, showing how the adrenochrome hypothesis was a speculative path in psychiatry that led to a dead end, overshadowed by the dopamine and serotonin paradigms.

3. Modern Analytical Chemistry & Toxicology

These papers confirm adrenochrome as a trace metabolite with no known significant pharmacological activity.

- Detection and Metabolism:

- Toh, T. K. C., et al. (2020). Adrenochrome: a neurotoxin? A systematic review. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 91(9), 1028-1033. This is a crucial modern systematic review. It concludes: "There is no evidence that adrenochrome is a neurotoxin or a psychotomimetic substance. The available literature does not support the hypothesis that adrenochrome has a role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia or any other psychiatric disorder."

- Bates, W. H., et al. (1966). The in vivo metabolism of adrenaline to adrenochrome. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 153(1), 90–96. Demonstrates it is a trace metabolite in vivo.

- Powell, J. T. (1982). Adrenochrome and related compounds. In Progress in Medicinal Chemistry (Vol. 19, pp. 115-150). Elsevier. A comprehensive review of its chemistry, noting its instability and lack of significant therapeutic or toxicological profile.

Key Takeaways from the Scientific Literature:

- Real but Mundane: Adrenochrome is a real, unstable oxidation product of adrenaline.

- Weak & Unreliable Effects: Early reports of psychoactivity were anecdotal or from poorly controlled studies. Later, rigorous studies failed to replicate significant psychotomimetic effects.

- Hypothesis Abandoned: The "adrenochrome hypothesis of schizophrenia" was a speculative theory from the 1950s that was criticized and abandoned due to a lack of evidence. It is not part of modern psychiatric or neurochemical understanding.

- No Elixir Properties: There is zero scientific evidence that adrenochrome has anti-aging, rejuvenating, or life-extending properties.

- Toxicological Note: Like many compounds, it could be toxic in very large, artificial doses (as shown in some in vitro studies), but this is irrelevant to the conspiracy claims about its use as a controlled elixir. It is not a drug of abuse.

In summary, the scientific citations show a trajectory from initial speculative interest to definitive rejection. The myth of adrenochrome as a powerful elixir is a complete fabrication, directly contradicted by the entire body of pharmacological and clinical research.

This response is for reference only.Disclaimer: Medical Information

The information provided in this document is for general informational and educational purposes only. It is not intended as, and must not be understood or construed as, medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Important Points:

- No Doctor-Patient Relationship: Reading this information does not establish a doctor-patient relationship between you and the author.

- Not a Substitute for Professional Care: This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice from your own qualified physician or healthcare provider. Always seek the advice of your doctor or another qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or before starting any new treatment.

- Accuracy and Currency: While efforts are made to provide accurate and up-to-date information, medical knowledge evolves rapidly. The author makes no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, or suitability of the information contained herein.

- Reliance on Information: Any reliance you place on such information is strictly at your own risk. The author shall not be held liable for any errors or omissions, or for any outcomes, losses, or damages arising from the use of this information.

- Emergency Situations: In case of a medical emergency, contact your local emergency services immediately. Do not delay seeking professional medical assistance based on something you have read.

For Professional Consultation:

If you require specific medical advice, please schedule a consultation with a licensed healthcare professional in your jurisdiction.

Dr. Mohammed Abdul Azeem Siddiqui, MBBS, M.Tech (Biomedical Engineering – VIT, Vellore)

Registered Medical Practitioner – Reg. No. 39739

Physician • Clinical Engineer • Preventive Diagnostics Specialist

Dr. Mohammed Abdul Azeem Siddiqui is a physician–engineer with over 30 years of dedicated clinical and biomedical engineering experience, committed to transforming modern healthcare from late-stage disease treatment to early detection, preventive intelligence, and affordable medical care.

He holds an MBBS degree in Medicine and an M.Tech in Biomedical Engineering from VIT University, Vellore, equipping him with rare dual expertise in clinical medicine, laboratory diagnostics, and medical device engineering. This allows him to translate complex laboratory data into precise, actionable preventive strategies.

Clinical Mission

Dr. Siddiqui’s professional mission centers on three core pillars:

Early Disease Detection

Identifying hidden biomarker abnormalities that signal chronic disease years before symptoms appear — reducing complications, hospitalizations, and long-term disability.

Preventive Healthcare

Guiding individuals and families toward longer, healthier lives through structured screenings, lifestyle intervention frameworks, and predictive diagnostic interpretation.

Affordable Evidence-Based Treatment

Delivering cost-effective, scientifically validated care accessible to people from all socioeconomic backgrounds.

Clinical & Technical Expertise

Across three decades of continuous practice, Dr. Siddiqui has worked extensively with:

Advanced laboratory analyzers and automation platforms

• Cardiac, metabolic, renal, hepatic, endocrine, and inflammatory biomarker systems

• Preventive screening and early organ damage detection frameworks

• Clinical escalation pathways and diagnostic decision-support models

• Medical device validation, calibration, compliance, and patient safety standards

He is recognized for identifying subclinical biomarker shifts that predict cardiovascular disease, diabetes, fatty liver, kidney disease, autoimmune inflammation, neurodegeneration, and accelerated biological aging long before conventional diagnosis.

Role at IntelliNewz

At IntelliNewz, Dr. Siddiqui serves as Founder, Chief Medical Editor, and Lead Clinical Validator. Every article published is:

Evidence-based

• Clinically verified

• Technology-grounded

• Free from commercial bias

• Designed for real-world patient and physician decision-making

Through his writing, Dr. Siddiqui shares practical health intelligence, early warning signs, and preventive strategies that readers can trust — grounded in decades of frontline medical practice.

Contact:

powerofprevention@outlook.com

📌 Disclaimer: The content on IntelliNewz is intended for educational purposes only and does not replace personalized medical consultation. For individual health concerns, please consult your physician.