What was discovered

- In 2020, a group of scientists at the Netherlands Cancer Institute reported finding a previously overlooked pair of salivary glands in humans.

- These glands have been named the “tubarial salivary glands” (or tubarial glands) because of their anatomical location near a cartilage structure called the torus tubarius.

Where are they located

- They lie deep in the upper throat (nasopharynx), behind the nasal cavity, over the torus tubarius.

- The torus tubarius is part of the auditory (Eustachian) tube’s opening into the pharynx.

Size and structure

- On average, the glands are about 3.9 centimeters (≈1.5 inches) in length.

- Histologically, they contain mucous gland tissue (with some serous acini), draining ducts, a capsule and trabeculae with blood vessels.

- They are bilateral (one on each side).

Function (hypothesized)

- The tubarial glands seem to contribute to lubrication and moistening of the nasopharyngeal area—i.e. the upper throat behind the nose and mouth.

- Their existence may help explain some complications in radiotherapy (for cancers in the head/neck region) such as dry mouth, difficulty swallowing, or speaking, when these glands are unintentionally damaged.

How they were discovered

- PSMA PET-CT imaging played a central role. PSMA (prostate-specific membrane antigen) is a protein used in imaging/tracer studies, especially in prostate cancer diagnostics. While using this imaging in patients, researchers noted uptake in a region of the nasopharynx that corresponded to glandular tissue.

- To confirm, they examined around 100 patients and also dissected two cadavers. All showed presence of the glands.

Why they had been missed until now

- The location is not very accessible and standard imaging methods (e.g. typical CT, MRI) don’t clearly show these glands. They may appear as “shadowy regions” of soft tissue.

- Only with more sensitive imaging (PSMA PET/CT) and focused anatomical/histological study were researchers able to identify them.

Questions / Controversies

- There is some debate in the scientific community whether these glands are truly a separate “new organ” or whether they may be grouped forms of minor salivary glands that simply had not been well characterized. CNN

- The initial studies had limitations: many patients imaged were male, many had cancer; more work is needed across broader populations (including healthy subjects, different ages, both sexes) to confirm the structure, function, variability. CNN+1

Significance

- For Oncology / Radiotherapy: If radiotherapists spare these glands during head/neck radiation, that could reduce side effects such as dry mouth, swallowing difficulties, and mucosal damage. Sky News

- Anatomical Knowledge: Enhances understanding of human anatomy; reminds that even in well-studied areas of the body, some structures may still be incompletely understood.

- Clinical Implications: There may be relevance in ENT (ear-nose-throat), oncology, radiology; potential for research into diseases, gland dysfunction, tumors in that region, etc.

Ongoing research & confirmation status for the Tubarial (Tubarial) Salivary Glands

Below is a concise, up-to-date review of where the science stands on the so-called tubarial salivary glands: what’s been done, what’s been challenged, and the most important next steps researchers are taking now.

1) Short recap of the original claim

In October 2020 a team led by the Netherlands Cancer Institute reported a previously unrecognized pair of macroscopic salivary-gland locations in the nasopharynx (over the torus tubarius) identified primarily by PSMA PET/CT imaging and supported by cadaver dissection and histology. The authors proposed the name tubarial glands and emphasized potential clinical importance for radiotherapy planning. ScienceDirect

2) What subsequent confirmation work has shown (2021–2025)

a. Histology and anatomical studies

- Several groups have performed targeted dissections and histological comparisons between tubarial tissue and known salivary glands. Multiple studies report mucous-type glandular tissue consistent with salivary function and describe a consistent bilateral location in many specimens, strengthening the anatomical case. Larger histological series and quantitative characterizations were published in follow-up papers. PMC+1

b. Imaging replication (PSMA PET/CT and other tracers)

- External validation studies using 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT and similar ligands have reproduced PSMA-avid areas in the nasopharynx in independent cohorts, confirming the imaging signature that initially highlighted these tissues. Some centers have reported the signal in both cancer patients and non-cancer patients. ScienceDirect+1

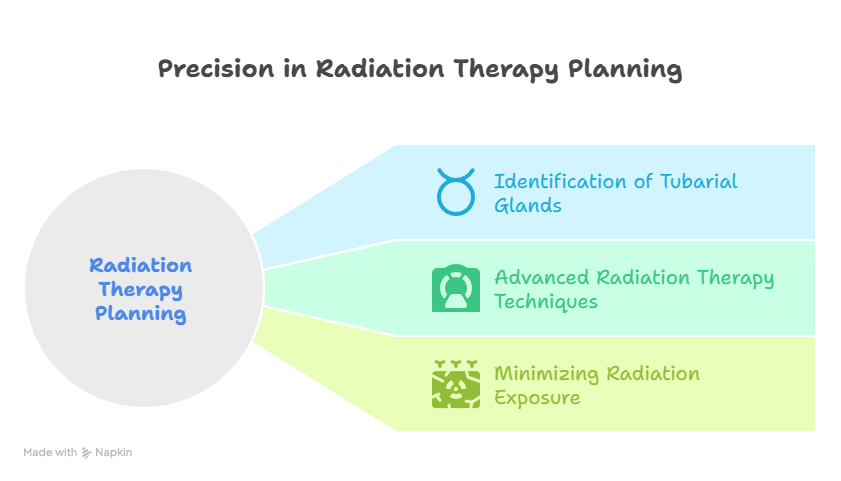

c. Clinical/radiotherapy studies

- Pilot dosimetric work shows it is feasible to contour and spare the tubarial region with modern radiotherapy planning (IMRT/proton therapy), and early dosimetric reports suggest potential reduction of dose to that region. Larger prospective outcome studies to link sparing with reduced symptoms (xerostomia, dysphagia) are underway or being planned. PubMed+1

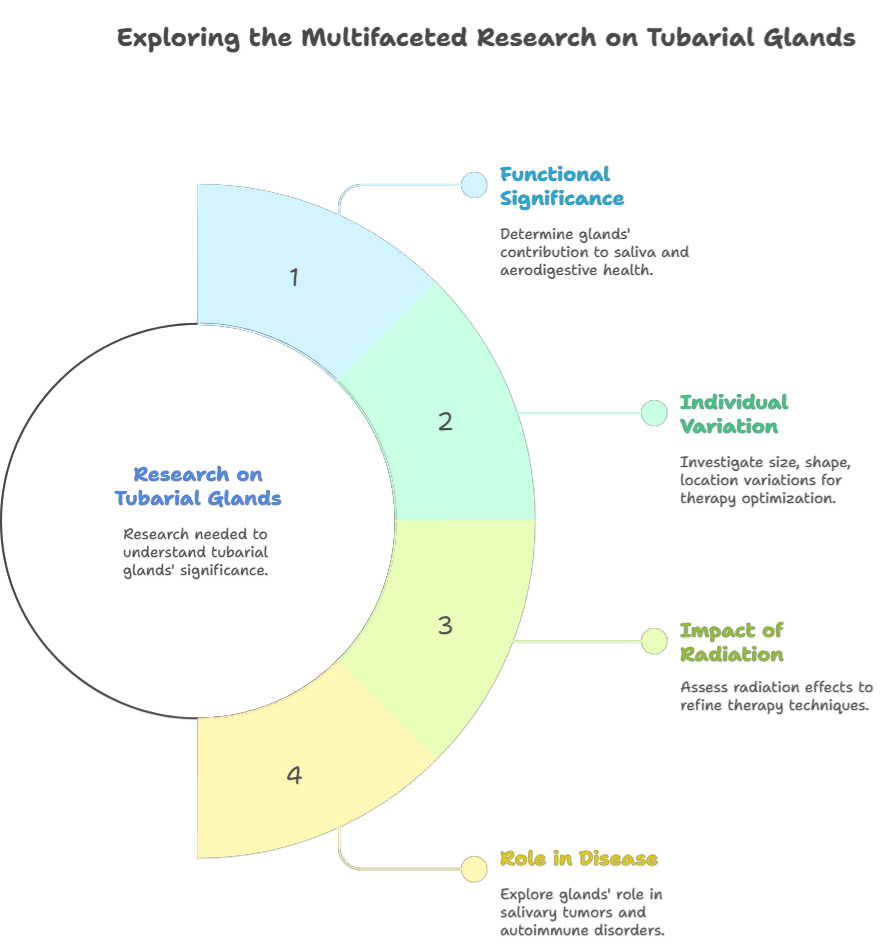

3) Major criticisms and remaining uncertainty

- Is it truly a “new organ” or an anatomical subset of minor salivary glands? Several anatomists and clinicians argue the tubarial tissue may represent a previously under-characterized aggregation of minor salivary glands rather than a wholly novel organ. This conceptual debate affects nomenclature and the degree of perceived novelty. ResearchGate+1

- Sampling and population bias in early work. The discovery cohort included many cancer patients and mostly males; critics ask for larger, population-diverse sampling (age, sex, healthy controls) to map variability. scholarly.unair.ac.id

- Functional proof is incomplete. Imaging and histology show glandular tissue and tracer uptake; however, definitive physiological measurements (e.g., stimulated saliva production directly attributable to these glands, molecular secretome profiling) are limited. Correlating gland dose with specific functional endpoints remains a work in progress. PMC

4) Ongoing and near-term research activities (what labs are doing now)

- Larger anatomical/histological series — multi-center cadaveric and surgical specimen studies to define frequency, size ranges, microanatomy, sex differences and age-related changes. PMC

- Imaging validation across tracers and scanners — reproducibility studies using 68Ga-PSMA, 18F-PSMA, and other radiotracers; cross-validation with MRI/ultrasound where possible. ScienceDirect+1

- Physiological and molecular assays — attempts to collect secretion (when surgically accessible) for biochemical analysis, to show mucin/enzymatic profiles and to confirm secretory function distinct from neighboring glands. PMC

- Prospective radiotherapy trials and dosimetry studies — randomized or cohort studies that intentionally spare the tubarial region to test whether sparing reduces specific side effects (xerostomia, nasopharyngeal dryness, dysphagia), and to define dose-response relationships. Early pilot dosimetry and proton vs IMRT comparisons have been published; clinical outcome data are still maturing. PubMed+1

- Pathology case reports / tumor registry surveillance — monitoring whether primary malignancies originate in the tubarial tissue (rare case reports exist) and whether tubarial tumors behave like other salivary gland neoplasms. ijashnb.org

5) Key findings so far (summary with citations)

- The initial PET/CT signal and cadaver evidence are reproducible in independent centers, confirming a consistent bilateral nasopharyngeal glandular structure. ScienceDirect+1

- Histological series show mucous gland tissue comparable to salivary glands, supporting classification as salivary tissue (though the “organ” label is debated). PMC+1

- Dosimetric planning to spare the region is technically feasible and proton therapy may spare it better than IMRT; however, robust clinical outcome evidence demonstrating measurable patient benefit is still limited. PubMed+1

6) Recommended next-step experiments (what would settle the major questions)

- Population anatomical atlas: systematic PSMA PET/CT (and MRI) imaging of a large, healthy, demographically diverse cohort to determine prevalence, bilateral symmetry, size distributions and normative values.

- Physiological secretion studies: intraoperative or biopsy-based collection of secretions + proteomic/mucin profiling versus parotid/submandibular secretions to establish distinct functional signatures.

- Dose-response clinical trial: randomized clinical trial in head & neck radiotherapy where one arm includes explicit tubarial sparing with pre-specified dose constraints and validated patient-reported and objective saliva/swallow endpoints.

- Longitudinal pathology surveillance: registry to capture rare tubarial neoplasms and their behavior relative to other salivary carcinomas.

- Standardized nomenclature and atlas publication: multidisciplinary consensus (anatomy, ENT, radiation oncology, radiology) on naming and contouring guidelines for clinical trials and atlases.

7) Practical implications for clinicians today

- Radiation oncologists may consider identifying and contouring the tubarial region when planning nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal radiotherapy; pilot work supports feasibility but definitive evidence that sparing improves outcomes is still pending. PubMed+1

- ENT and radiology teams should be aware of the region as a possible source of nasopharyngeal glandular lesions and interpret PSMA uptake in the nasopharynx in that context. ScienceDirect

8) Bottom line

The tubarial region is now well-recognized as containing consistent glandular tissue visible on advanced PSMA PET imaging and confirmed by histology in multiple follow-up studies. The major remaining question is semantic/functional: whether this tissue constitutes a distinct “new organ” or an aggregation of minor salivary glands — and, more importantly for patients, whether deliberate sparing of this tissue during head/neck radiotherapy provides clinically meaningful benefit. Ongoing multi-center anatomical, physiologic and prospective radiotherapy trials are the crucial next steps to turn promising early findings into evidence-based clinical practice. ScienceDirect+2PMC+2

Conclusion

The discovery of the tubarial glands is a fascinating development in anatomy and medicine. While they may not revolutionize physiology textbooks overnight, their recognition could improve patient care (especially for head/neck cancers), add detail to the map of human salivary systems, and provoke further study into similar “hidden” structures.

****************************************************************************************

Disclaimer: Dr. Mohammed Abdul Azeem Siddiqui, MBBS

Registered Medical Practitioner (Reg. No. 39739)

With over 30 years of dedicated clinical experience, Dr. Siddiqui has built his career around one clear mission: making quality healthcare affordable, preventive, and accessible.

He is deeply passionate about:

- Early disease diagnosis – empowering patients with timely detection and reducing complications.

- Preventive healthcare – guiding individuals and families towards healthier, longer lives through lifestyle interventions and screenings.

- Affordable treatments – ensuring cost-effective, evidence-based medical solutions that reach people from all walks of life.

Through his blog, Dr. Siddiqui shares practical health insights, early warning signs, and preventive strategies that readers can trust. Every article is rooted in evidence-based medicine and enriched by decades of hands-on clinical practice.

Contact us on: powerofprevention@outlook.com

📌 Disclaimer: The content in this blog is for educational purposes only and should not replace personalized medical consultation. For specific health concerns, please consult your physician.

Dr. Mohammed Abdul Azeem Siddiqui, MBBS, M.Tech (Biomedical Engineering – VIT, Vellore)

Registered Medical Practitioner – Reg. No. 39739

Physician • Clinical Engineer • Preventive Diagnostics Specialist

Dr. Mohammed Abdul Azeem Siddiqui is a physician–engineer with over 30 years of dedicated clinical and biomedical engineering experience, committed to transforming modern healthcare from late-stage disease treatment to early detection, preventive intelligence, and affordable medical care.

He holds an MBBS degree in Medicine and an M.Tech in Biomedical Engineering from VIT University, Vellore, equipping him with rare dual expertise in clinical medicine, laboratory diagnostics, and medical device engineering. This allows him to translate complex laboratory data into precise, actionable preventive strategies.

Clinical Mission

Dr. Siddiqui’s professional mission centers on three core pillars:

Early Disease Detection

Identifying hidden biomarker abnormalities that signal chronic disease years before symptoms appear — reducing complications, hospitalizations, and long-term disability.

Preventive Healthcare

Guiding individuals and families toward longer, healthier lives through structured screenings, lifestyle intervention frameworks, and predictive diagnostic interpretation.

Affordable Evidence-Based Treatment

Delivering cost-effective, scientifically validated care accessible to people from all socioeconomic backgrounds.

Clinical & Technical Expertise

Across three decades of continuous practice, Dr. Siddiqui has worked extensively with:

Advanced laboratory analyzers and automation platforms

• Cardiac, metabolic, renal, hepatic, endocrine, and inflammatory biomarker systems

• Preventive screening and early organ damage detection frameworks

• Clinical escalation pathways and diagnostic decision-support models

• Medical device validation, calibration, compliance, and patient safety standards

He is recognized for identifying subclinical biomarker shifts that predict cardiovascular disease, diabetes, fatty liver, kidney disease, autoimmune inflammation, neurodegeneration, and accelerated biological aging long before conventional diagnosis.

Role at IntelliNewz

At IntelliNewz, Dr. Siddiqui serves as Founder, Chief Medical Editor, and Lead Clinical Validator. Every article published is:

Evidence-based

• Clinically verified

• Technology-grounded

• Free from commercial bias

• Designed for real-world patient and physician decision-making

Through his writing, Dr. Siddiqui shares practical health intelligence, early warning signs, and preventive strategies that readers can trust — grounded in decades of frontline medical practice.

Contact:

powerofprevention@outlook.com

📌 Disclaimer: The content on IntelliNewz is intended for educational purposes only and does not replace personalized medical consultation. For individual health concerns, please consult your physician.